In December 2021, the American Battlefield Trust purchased 245-acres of the Williamsburg Battlefield known today as the Egger Tract and as the Custis Farm during the Civil War. This acreage encompasses the entire afternoon phase of the May 5, 1862 Battle of Williamsburg. The successful acquisition was a decade in the making and required coordination and cooperation between many parties as well as the largest single grant in the American Battlefield Protection Program’s history, suggesting just how important preservation of this tract was viewed.

““People in Williamsburg have been caring about this property for so long. I will tell you that if any one of our parts had failed the house of cards would have come down. This is a big win.””

Image from Google Maps

location

Located in York County, VA, the Egger Tract is bounded on the west by Interstate-64, on the north by the Colonial National Historical Parkway, on the east by property of the U.S. Navy (Cheatham Annex), and on the south by additional battlefield property owned by the American Battlefield Trust and known as the Busch Tract. Bisecting the property from southwest to northeast is the abandoned roadbed of the old Queens Creek Road. The entirely forested land is level and rises gently as you approach the Colonial Parkway along the old roadbed. There are several ravines and spring-fed streams on the property to either side of the roadbed. The streams on the eastern side feed into Jones Pond and those on the west flow into Queens Creek to the north.

Historical Significance

(The following historical and military summary of events concerning the Egger Tract is based on research by John F. Cross III and Thomas L. McMahon and presented in their 2004 unpublished Fouace’s Quarter & James W. Custis Farm report.)

The Egger Tract has cultural and historical resources related to Native American occupation prior to European contact, farmsteads and plantations from the 17th through 19th-centuries, and the 1862 Battle of Williamsburg. Stephen Fouace, a French Huguenot and original trustee of the College of William & Mary, acquired the property in the 1690s and maintained a farm there. He returned to England about 1704 and rented and then sold his land holdings to the Burwell family, who through marriage inherited Carter’s Grove Plantation on the James River and other vast land holdings in York County. These land holdings were divided into smaller, more manageable parcels or “quarter farms.” Quarters were worked by slaves and managed by overseers who lived on the property and were usually paid in a share of the farm produce. While not the largest of the five quarters, Fouace’s was the most productive by the late 18th-century. A 1782 map drawn by French military cartographer Jean Nicolas Desandroüin shows Fouace’s Quarter with at least six structures on the east side of Queens Creek Road and three on the west side. These would have included an overseer’s house, slave quarters, barns, and support structures. After Nathaniel Burwell’s death in 1814, Fouace’s Quarter likely passed through several owners. Land tax records indicate that James W. Custis, who served in the Virginia State Senate and House of Delegates, was paying taxes on Fouace’s Quarter by 1853. He did not live on the property and instead resided in Williamsburg in what is known today as the William Finnie House. It was at this time that the land became known as the Custis Farm.

Desandroüin’s Map of 1782 Showing Fouace’s Quarter with Approximate Boundaries of Egger Tract (Map Courtesy of Library of Congress)

Battle of williamsburg

In 1861, the Confederate Army constructed a line of defensive works across the Peninsula at Williamsburg. Fourteen redoubts extended from Tutter’s Mill Pond northeast to Queens Creek. Beginning at Fort Magruder, the central and largest redoubt, the entire left flank of the fortified line ran northeast along Queens Creek Road. Redoubts 8, 9, 10, 11, and 14 were built on or near the Custis Farm property. Redoubt 11 still survives on the property in excellent condition where the old Queen’s Creek Road meets the Colonial Parkway.

When the Confederate Army was withdrawing up the Peninsula from Yorktown on May 4, General Joseph Johnston had no intention of occupying the Williamsburg defenses. An unexpectedly energetic pursuit by Union cavalry, though, precipitated the need for General James Longstreet’s division to turn around and fight a rear-guard action at Williamsburg. For reasons unknown, Redoubts 11 and 14 went unoccupied, leaving the left flank of the Confederate line wide open to attack. On the morning of May 5, at least 16 runaway slaves (possibly from the Custis Farm) informed Union commanders of the unoccupied redoubts. During the early afternoon, Union General Winfield Scott Hancock was sent with five regiments and ten guns to occupy the vacant redoubts, which he did without resistance. Then pushing south on Queens Creek Road to shell Fort Magruder and Redoubts 9 and 10, which were occupied by South Carolina troops, he placed his artillery on the Custis Farm with several guns inside the fenced yard of the farmhouse. Union skirmishers were sent out in front of the guns while the regiments were positioned around the farm buildings and Redoubt 11.

Map Courtesy of the American Battlefield Trust (www.battlefield.org)

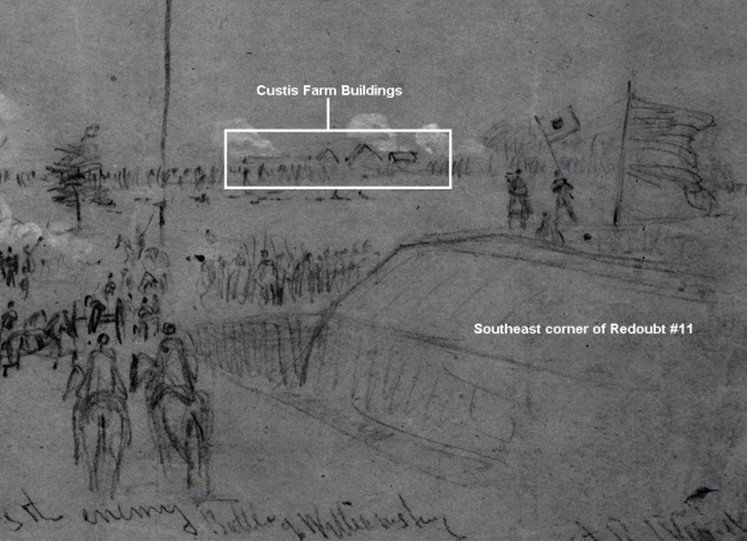

This arrangement of Union troops remained generally unmolested for several hours. Late in the afternoon, though, Hancock’s artillery fire drew interest and Confederate commanders realized their blunder. Four infantry regiments with no artillery support under General Jubal Early were sent to attack Hancock’s forces. Marching towards the sound of the guns through dense woods and ravines, the regiments became separated and only two reached the Custis Farm. The 24th VA emerged into the open farmland first just north of the farm buildings and rushed forward through the farmyard, knocking down the fencing, to try to capture the Union guns. The 5th NC emerged next but several hundred yards south of the 24th VA. While under fire, it crossed the open distance to support the 24th VA. By now, Hancock had pulled back his artillery and infantry, aligning them on both sides of Redoubt 11 to face the on-coming Confederate attack. The Confederates rashly pushed on across the open fields of green wheat shoots to a fence line 40 yards in front of Redoubt 11 where they halted and began to exchange fire with the Union forces. In short order, Union superiority in numbers and ordnance took a terrible toll, and the rebels withdrew. The ill-advised, piecemeal Confederate attack was repulsed with horrible losses. From his part in the battle, General Hancock won his sobriquet, “Hancock the Superb,” which was taken from a telegraph relaying the results of the battle in which General George McClellan indicated “Hancock was Superb.”

Partial Image of “Hancock’s Brigade Repulsing the Enemy. Battle of Williamsburg” by Alfred R. Waud and Published in Harper’s Weekly May 24, 1862 (Image Courtesy of Library of Congress)

Aftermath

After the Confederate retreat, the Custis Farm was left in the hands of Union forces, and Hancock was reinforced. The Confederate wounded and prisoners were herded into Redoubt 11 during the night, and the following day, the Custis Farm buildings became a field hospital. Two days after the battle Casper Dean of the 6th Vermont Regiment wrote, “When we took Hancock’s position, the ground near to us was strewn with dead and wounded rebels. The sight was a horrible one. Our men were busy all day in burying the dead and taking care of the wounded rebels. 175 wounded rebels were taken to two large barns, and our surgeons dressed their wounded. A great many limbs were amputated.” The bodies of the soldiers killed in action were buried on the field as well as those of soldiers who subsequently died of wounds at the farm. There is a strong possibility the Egger Tract still contains the graves of these Confederates soldiers. An attempt was made to locate and remove the Union dead from the Williamsburg Battlefield in 1867, but there is no record of any attempt to remove the Confederate dead.

Custis Farm Buildings Used as Hospitals Following the Battle (Original Image Source Unknown)

Preservation effort

Early 20th-century maps show no structures surviving on the now reforested land, and other than some logging and hunting, the land rested quietly in pristine condition. Then, in the early 21st-century, the Egger Tract experienced a new battle between developers and preservationists, who had to overcome the whopping $9.2 million value of the land to claim victory. A $4.6 million National Park Service American Battlefield Protection Program grant was key to the successful purchase of the property. Additional grants were provided by the Virginia Battlefield Preservation Fund, the Virginia Land Conservation Foundation, and the U.S. Department of Defense’s Readiness and Environmental Protection Integration Program. The American Battlefield Trust also received donations from its members and the public.

future benefits & plans

The Egger Tract is now protected by a perpetual historic preservation and open-space easement held by Virginia’s Department of Historic Resources, whose Director Julie V. Langan stated, “This easement preserves and protects a vital array of historic and archaeological resources important to all Virginians’ history.” In the future, the Department of Historic Resources, American Battlefield Trust, and Williamsburg Battlefield Association would like to see public archaeology performed on the site, improved public access, amenities constructed for programming and educational purposes, restoration of the landscape to its 1862 appearance, and addition of walking trails, interpretive signage, and exhibits. There is even the hope of a rail-to-trail connection between the Egger, Busch, and Smith Tracts.

Outside Redoubt 11 on the Egger Tract in Fall 2022 (Image Courtesy of American Battlefield Trust)